The Fundamental Problem

You've already reached your conclusion.

Caption: Claude Shannon, American mathematician, electrical engineer, computer scientist, cryptographer.

It began with signal loss

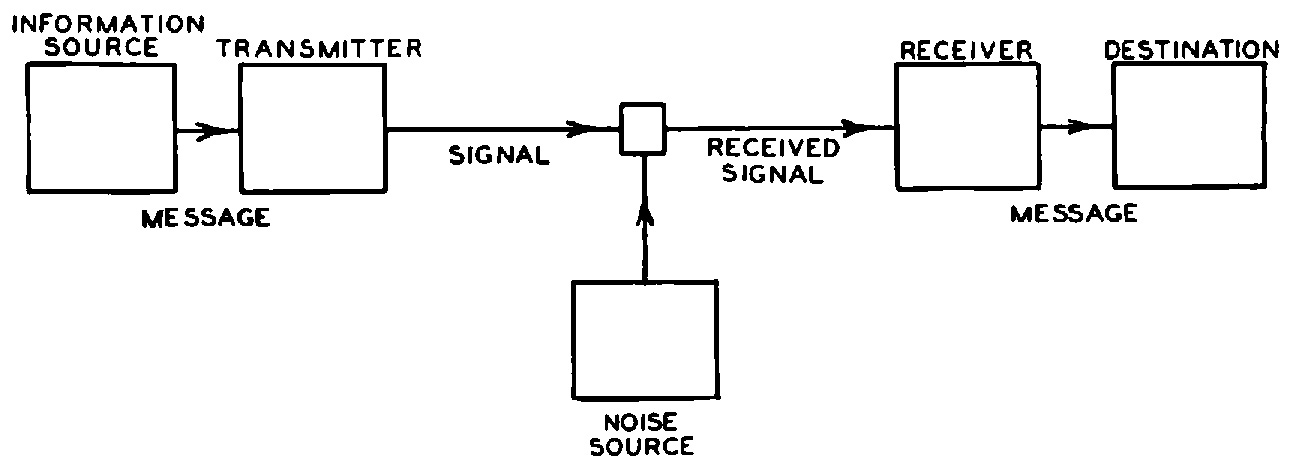

In the opening of his foundational 1948 paper, “A Mathematical Theory of Communication,” Claude Shannon established the premise for the entire field of information theory, a fundamental branch of both signal processing and communications.

“The fundamental problem of communication is that of reproducing at one point, either exactly or approximately, a message selected at another point”.

Digital communication amplifies the problem, now we face an environment where neither the starting point, conduit, or destination (either exactly or approximately) are knowable.

A schematic diagram of Shannon’s model of communication.

Let’s go back to the early internet

Memes provide a glimpse into the origins of how and why communication begins to breakdown through loss of signal. Memes develop patina through signal loss while gaining viral authenticity from consistent reproduction. Signal loss becomes the meme itself and increases the intrinsic value of the pixels we see. This is intentionally, and unintentionally, becoming a model for communication across media.

Early memes were limited by the web technology and bandwidth of the era. The Graphics Interchange Format (GIF) was prevalent for its animation capabilities but limited to a 256-color palette. The JPEG format, while supporting a broader color range, used lossy compression that degrades image quality with every resave.

The low resolution of early memes became a hallmark of their viral authenticity, signaling that the image had been organically passed around by many users. Deep-fried and nuked memes, intentionally took this a step further by over-compressing images to the point of extreme pixelation and color distortion for comedic effect.

The paradox of improving technology

As internet speeds and display resolutions improve, the degradation of communication rapidly progresses, creating a stark contrast between a meme’s low-quality appearance and the high-definition devices used to view it.

In the same way that social media automatically compresses images to save bandwidth, communication of all forms is experiencing a further loss in quality every time anything is shared.

The deep-fried meme aesthetic evolved from a technological limitation into an art form. Aggressive artifacting became a visual signifier of the joke itself, and the commentary on the absurd and chaotic nature of online culture created a model for the slippery slope we find ourselves sliding down both socially and commercially.

(Caption: Wisdom Conquering Ignorance, Aegidius Sadeler II, after Bartholomaeus Spranger)

Where things break down

The differences between human speech and other types of communication provide clues to the breakdown of comprehension. It’s important to distinguish between two concepts: information rate (the amount of new information conveyed) and frequency bandwidth (the range of frequencies a channel can carry). Human communication is remarkably low-bandwidth in terms of raw information but complex in its analog form, while modern digital communication uses significantly higher bandwidth to send data.

Human speech is an analog signal that contains two types of information:

Semantic information (low bandwidth): Studies suggest that spoken language conveys a remarkably consistent average rate of about 39 bits per second (bps) across different languages. This semantic content—the actual words being spoken—is highly redundant, meaning it can be transmitted using very little raw data.

Emotional and vocal information (higher bandwidth): The frequency and character of a voice carry extra information, such as emotion, emphasis, and speaker identity. This is why telephone calls, which filter out many of these nuances, sound less rich and are more prone to misunderstanding.

In contrast to the very low semantic information rate of human speech, modern digital formats can transmit vast amounts of data. This is partly because they digitize all frequencies, and in the case of video, add visual information.

The differences

Analogue vs. Digital: Human speech is an analogue signal whose bandwidth is based on the range of frequencies it occupies. Digital communication converts information into binary data, and its bandwidth is the bit rate—the number of bits transferred per second.

Efficiency vs. Fidelity: The complexity of digital communication comes from its quest for perfect fidelity, not just delivering the message. Where a low-bandwidth voice channel might be “good enough” to understand the words, a high-definition video stream captures millions of pixels of information per second to create a lifelike viewing experience.

Compression: All digital communication formats use compression to save bandwidth. For example, text files are highly compressible because language is redundant. Video uses sophisticated algorithms to reduce file size without a noticeable loss of quality.

Human speech is efficient at conveying complex, multi-layered information using a tiny data rate compared to digital formats. We perceive it as complex, but a large part of that is our brain’s sophisticated processing, not the raw bandwidth required to transmit the words themselves. Digital communication, on the other hand, relies on much higher bandwidth to achieve a high degree of fidelity. As digital communication replaces human interaction we come face to face with the reality of Shannon’s hypothesis: “The fundamental problem of communication is that of reproducing at one point, either exactly or approximately, a message selected at another point.” Signal loss is a byproduct of the medium, and preventing complex and nuanced nature of human interactions.

Filling in the lost signal

When the signal is degraded, whether intentionally or naturally, the human brain uses its natural processing mechanisms to reconstruct meaning.

Psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s concept of “What You See Is All There Is” (WYSIATI) explains that our brains construct a coherent narrative based on the information immediately available, without dwelling on missing data. In online communication, where context is often scarce, this bias is rampant. We see a snippet of a conversation, a screenshot, or a meme, and our brain quickly fills in the gaps to create a complete story. This is a crucial source of modern digital confusion.

The overwhelming volume of information online, forces the brain to take cognitive shortcuts. Memes are, in effect, highly efficient compression algorithms for ideas, emotions, and cultural references. By leveraging shared knowledge and cultural codes, they allow for rapid communication, reducing cognitive load. This can be compared to the brain’s use of stereotypes to fill in missing information. It is an efficient, but deeply flawed, process.

Our interpretation of a low-fidelity meme is similar to how we processes speech. While a telephone call loses vocal nuances (a form of “signal loss”), the listener’s brain works to infer emotion and intent from the limited audio. Similarly, a compressed meme’s artifacting prompts the viewer’s brain to reconstruct the original image while simultaneously interpreting the social and cultural “noise” that has been added. The signal loss doesn’t end communication; it changes the interpretive task.

For instance:

Aoccdrnig to a rscheearch at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy, it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe.

It is possible to read incomplete words because the human brain uses contextual clues and a process called “top-down processing” to fill in missing information. Our minds are good at recognizing patterns and do not require every letter to be in place to understand a word.

How the brain processes missing information

Top-down processing is a cognitive process where the brain uses prior knowledge and context to predict and interpret sensory information. Instead of relying solely on the incoming visual data (bottom-up processing), the brain uses surrounding words and past experiences to infer the full meaning of an incomplete word.

For familiar words, the brain recognizes their general shape and length, rather than parsing them letter-by-letter. The overall outline of the word acts as a recognizable image, which is why a word like “c_t” is immediately identified as “cat”.

The surrounding text provides powerful clues that restrict the number of possibilities for a missing word. For example, in the sentence “The doctor prescribed some m_di_i_e,” the surrounding words make it highly probable that the incomplete word is “medicine”.

How easily you can read an incomplete word depends on its frequency and familiarity. You can easily recognize the jumbled or missing letters in a high-frequency word, but you will need more time to process a less common or less predictable word.

From noise to misinformation

The process of reading an incomplete word is a microcosm of a social phenomenon. Our mind fills in the blank instinctively based on context. However, when the context is corrupted or intentionally manipulated, whether by a noisy signal, an emotionally charged moment, or a malicious actor, the brain’s heuristic for filling in the blanks leads to profound and systemic breakdowns in communication and the spread of misinformation.

Social media algorithms act as powerful semantic filters, intentionally amplifying certain types of information and suppressing others, creating an echo chamber effect. This is a form of signal processing. By removing alternative or dissenting viewpoints, the algorithm degrades the overall information signal available to the user, who then uses their WYSIATI bias to assume the limited information they receive is the complete picture.

Because memes are culturally compressed and emotionally resonant, they are highly effective vehicles for misinformation. The emotional salience of the meme can override the need for factual accuracy. The meme’s very design, relying on the viewer to fill in the missing context, makes it difficult to fact-check. The joke and the propaganda become indistinguishable by design.

The traditional hierarchy of information, based on source, integrity, and fidelity has been inverted. Simultaneously, the “authentic,” low-resolution, viral meme often carries more social weight and is treated with more credibility than a high-fidelity, polished report; thereby diminishing comprehension of accurate information. The intentional loss of the signal, a once undesirable outcome, has been re-encoded as a signifier of truth and authenticity in the digital age.

I agree with half of what the author says.